We all know the old adage: “There’s no accounting for taste.” Account, meaning “a statement explaining one's conduct.” In 2023, in this world where capital has totalized everything, in particular, aesthetics, it might be time to finally read accounting as “the system of recording and summarizing business and financial transactions and analyzing, verifying, and reporting the results” instead.

Sure, Elizabeth Gaskell popularized the idea that money can’t buy taste, as in cash doesn’t equate class; but in 2023, social capital isn’t the urgent variable here. We’re set with hierarchies, they’re a fixture. I see the adage as a declaration: no ledger for taste exists. Money doesn't need critical judgment.

Accounting has become the backbone of the art world. Transactions make art move.And we’re seeing a somewhat novel—or at least unfamiliar—phenomenon, where in turn, the totalized financialization of art has by and large removed aesthetic judgment from the public conversation.

Larry Gagosian doesn't get paid to talk about art, after all. The cries that criticism has been incised from the conversation are a decade (if not longer) old by now. Now it’s being declared a crisis!; meanwhile the number #1 complaint fielded my way at gallery dinners, museum events, and global art biennials is: “everyone just asks, ‘how much is that?’”

Before being written off as mere crust-punk or anti-capitalist conjecture, or alternatively that art has no value but its intrinsic one... please. You think I’d lead you there? Patronage is essential for an art work to have a larger cultural impact—long equated with its value—and whether the acquisition of a work comes from a collector, organization or an institution, that’s inherently neutral. We should only evaluate from whom and where the money comes. And before anyone blames the art fairs, sorry, I was preemptively rolling my eyes.

In turn though, that allows all of us who toil in these chambers to do so. The more art that sells, the more people are employed, the bigger the value of the industry, the larger seat at the tables of power: seemingly that’s the natural progression of our capitalist system. There are benefits to this system! But we’ve witnessed something unexpected in acceleration over the last decade (and slowly over the last 50, as most art analysts point to the 1970s when the idea of art could be an alternative investment asset began to circulate, then in the ‘80s Wall Street got into the game): art for asset’s sake.

In any expansionary economic model, there has to be available goods in order to scale. In the accelerated post-2020 burst in the art business (pushing it past the $80 billion mark in 2022), emerging art became the way for dealers to capitalize on the demand they were seeing from their collectors, whose wealth grew enormously during the pandemic. Likely you know this. The conversation is well-trodden terrain in the press and person-to-person alike.

Still, the strongest example of the market-scaling tactics is in the Wet Paint category—often quickly produced for an art fair or gallery show, out of the studio and onto the Index. Sales data shows that Wet Paint corners about 20% of the contemporary market these days, and dealers need a stable of fresh, quickly produced works to keep up with selling opportunities from monthly exhibition programming to the bevy of global fairs. Artists now must keep up with the production pace to be part of the generative action. There wouldn’t be an aptly titled gossip column titled ‘Wet Paint’ (shout out to Annie Armstrong!) if the painting genre didn’t stick out for some reason. Who has time for discourse when there’s money to be made?

To claim that artists are making art work simply for a market is unfair, and untrue. That said, how many texts have so many of us received from an artist friend lamenting how their dealer asked them “to add more red” as the almost urban-legend phrase goes? Is this true, is this hearsay, do people just love to complain? All of the above! There are unsavory practices being deployed that take advantage of the world’s second largest unregulated market, and artists often are collateral.

So where does taste fit into all of this? Should we all be sitting around stroking our beards and quoting au current aesthetics texts instead? Eh, it’s always fun to pop into critical salons run at TJ Byrnes with Dean Kissick or the parties at Anna Delvey’s or openings at O'Flaherty's to debate art ideas with threateningly stylish Gen Z art bimbo goths. Gals, we thank you for your contribution! Taste is an elitist sport, and that’s very out of fashion these days. The chase of taste is a reminder of the urgency of beauty. At the moment, we don’t particularly live in beautiful circumstances.

Beauty is also a tricky concept. Beauty is hotly controversial in philosophy, but known when it’s experienced and “counted among the ultimate values, with goodness, truth, and justice,” says Stanford. Aesthetics is inherent to nature and the cosmos—one reason Aristotle employed symmetry as the basis of beauty. But beauty is fragile because of its subjectiveness. It’s ineffably felt.

And art and beauty have such an intertwined, inextricable relationship. They are siblings, best friends and they are foes and foils in each other’s stories. We don’t have space here to speed through the historical continuum of aesthetics as a discourse (just read Arthur Danto!); but what much of the post-war 20th century critics (Greenberg, Fried, Krauss) did was frame art to be above the quest of beauty, drawing from a Kantian view that beauty is a human construction, a projection of what one sees, therefore subjective (and thus political, the jump-off for Marxian & PostMod theory, too).By the ‘80s, if your work was deemed beautiful, that proved both an insult—and unsaleable.

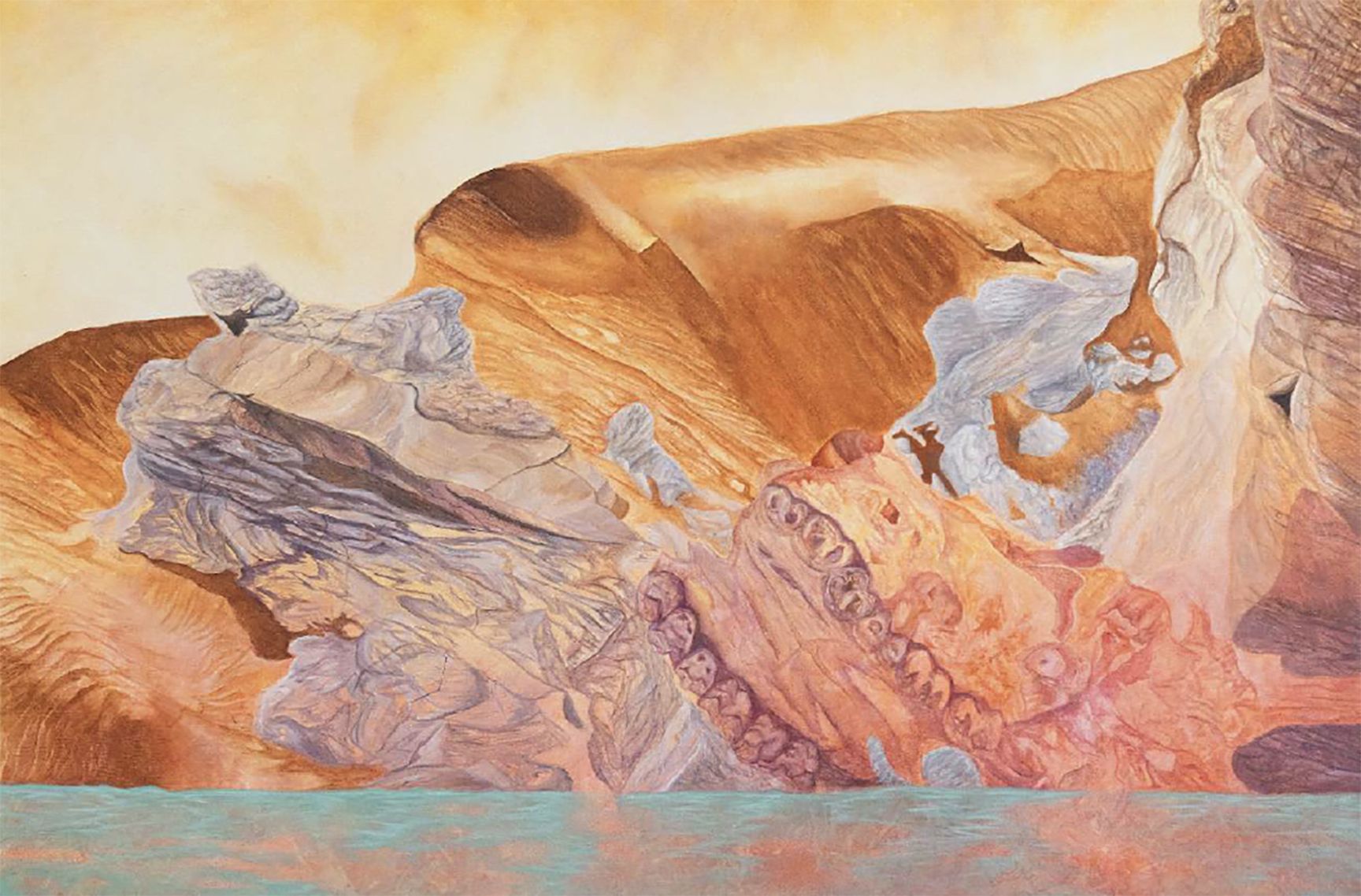

That attitude has largely prevailed in the contemporary art world (minus an impassioned blip in the mid-’90s from critics like Dave Hickey and Elaine Scarry). There’s still little pursuit of beauty in European Kunsthalles whose curatorial programming remains shaped by relational aesthetics; or in the street-art influenced collections of American tech titans. For beauty has been maligned in our capitalist era as easy, accessible, cheap—a sales trick. Its biggest advocate has been “the Schjeldahl effect,” the awe of seeing something and it moving you (by the way, “privileging the emotional” is having a great decade). We’ve even seen the rise of “ugly” art, catering to the abject and profane, a near-sexy subversive rejection of the primacy of beauty (that still centers beauty, all said—a delightful contradiction highlighted in the “Ugly Painting” show at Nahmad Contemporary curated by Kissick and Elayne Cayre.)

And it’s difficult work to strive for beauty. It is easier to consume than to produce. Beauty is more than just aesthetic appeal. I always return to Dostoveysky’s plea, “Beauty will save the world,” which in the context of 2023 sounds so stridently corny; but the Russian novelist wrote that after he survived a mock execution (“clemency” by the Tsar). The man’s life was a tragedy at every turn—he knew from suffering; and his plea derived not from fanciful imagination, but hopeful observation.

So how the hell can a parlance akin to“live, laugh, love” belong anywhere other than a screen-printed pillow from HomeGoods? Dostoyevsky meant that beauty is a virtue, an impetus towards the good and truth, one that inspires the best in humanity and connects us to each other. Sure, the innocent romanticism of 19th-century thinking feels dusty in these deeply fractured times, but maybe it’s in sincerity we can find meaning.

Acknowledging beauty is taste. Money doesn’t have those sensors, it can’t feel the awe. Taste is connection, to a person, to oneself, to something higher. Which is why there is no accounting for taste, beauty cannot be reduced to capital.

Is it fair to say that we’re in a moment where art is produced, experienced and acquired without its companion of beauty (that thing of truth and the cosmos)? I’m not looking to call the game, but it certainly feels like we’re edging towards its totalization too. If that’s the case, the whole enterprise of art renders as a commodity, and only a commodity.

It’s easy to point to the increase in environments in which art is sold, such as fairs or galleries, as the enabler this market madness—but lest you be tempted to cast aspersions, remember that fairs and galleries do their best at providing a curatorial context, a commitment to the art beyond just its price. That they've become sales spaces speaks to the culture of collecting right now.

Thus, the case for taste encapsulates the urgency in avoiding the entire reduction of art to commodity. Is beauty the answer? I don’t know; but it’s most certainly a virtue that time and again has inspired the good. We could aspire to more of that around here these days!

As a freelance writer and editor, Julie Baumgardner writes and covers the areas of art, design, travel, and all things cultural. Her work has been featured in Bloomberg, Fodor’s, New York Magazine, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and many other publications. Julie has also been interviewed for Miami Herald, Observer, Vox, USA Today, as well as worked on publications with Rizzoli press and spoken at art fairs and conferences.