Resplendent in a shimmering purple and cyan minidress dress, La Chola Poblete performs choreographed steps to a silent rhythm. Below her white high heeled shoes is a bed of Spanish-style Lays potato chips. Moving to music the audience cannot hear, La Chola’s attire is typical for women performing the Caporal, a traditional, popular Andean dance that originated in the Yungas region of Bolivia. The costumes for men were inspired by mixed-race slave masters known as Caporal, but they also have religious aspects. Gendered roles are also inscribed in the dance that is performed by both men and women, with men typically performing the more impressive parts.

In La Chola’s response to the Caporal – titled American Beauty – the artist shifts the focus to the market and its categorisation of artists. “I question my identity and how I fit into the system. Dancing on capitalism, I am asking myself if I'm gay, mestizo, transvestite, transsexual – or all four? What caste denomination do I belong to? Can a woman, daughter of a mestizo and an Indian turn and jump, or do other types of movements in a macho dance?”

La Chola and I exchange words in Spanish from her studio in a former mansion in San Telmo, a picturesque and well-preserved neighbourhood in Buenos Aires, characterized by colonial buildings and cobblestone streets. Born in Guaymallen, Mendoza, the geography and cultures of her mixed heritage is central to La Chola’s works – which include performances and action, photographs, and paintings. Her maternal line comes from Bolivia, and on her father’s side, Chile. Growing up in Argentina, she was discriminated against for her indigenous features “more so than for my sexual orientation... For a long time, I denied my roots, but thanks to art, I’ve made friends with myself.” She continues, “I decided to tell my story and raise the flag for being different. I am above all a dissident artist.”

Central and persistent in that story is the protagonist of La Chola, a term often used to pejoratively refer to women of mixed Spanish and indigenous ancestry. The artist reclaims this figure as a mysterious, mythological, and maternal – paying tribute to the women of the artist’s family but also arising from the “desire to have another identity, to be feminine, as I am now. If anyone asks me if I’ve transitioned, I say yes… through my work.” In early photo-performances, La Chola dons her grandmother’s sweaters and skirts, her hair woven into thick braids by her mother and sister in an intimate ritual.

When the Chola figure has appeared in art history, she has been seen by men: Goya’s The Nude Maja (1797-1800) is an historic example, a painting that in turn inspired the Argentine artist Alfredo Guido to execute his La Chola Nude (1924), in which a white-passing woman reclines against a background of tropical fruits, Andean fabrics, and folkloric objects that point to an ancestry not traceable in the subject’s features: “an attempt to revaluate the indigenous,” La Chola Poblete explains. It speaks of a narrative that the artist sees as prevalent in her country still today. “Most Argentines say that their grandparents got off the boats and thus erase the past that inhabited this territory. But Argentina is mestizo and brown, not just white.”

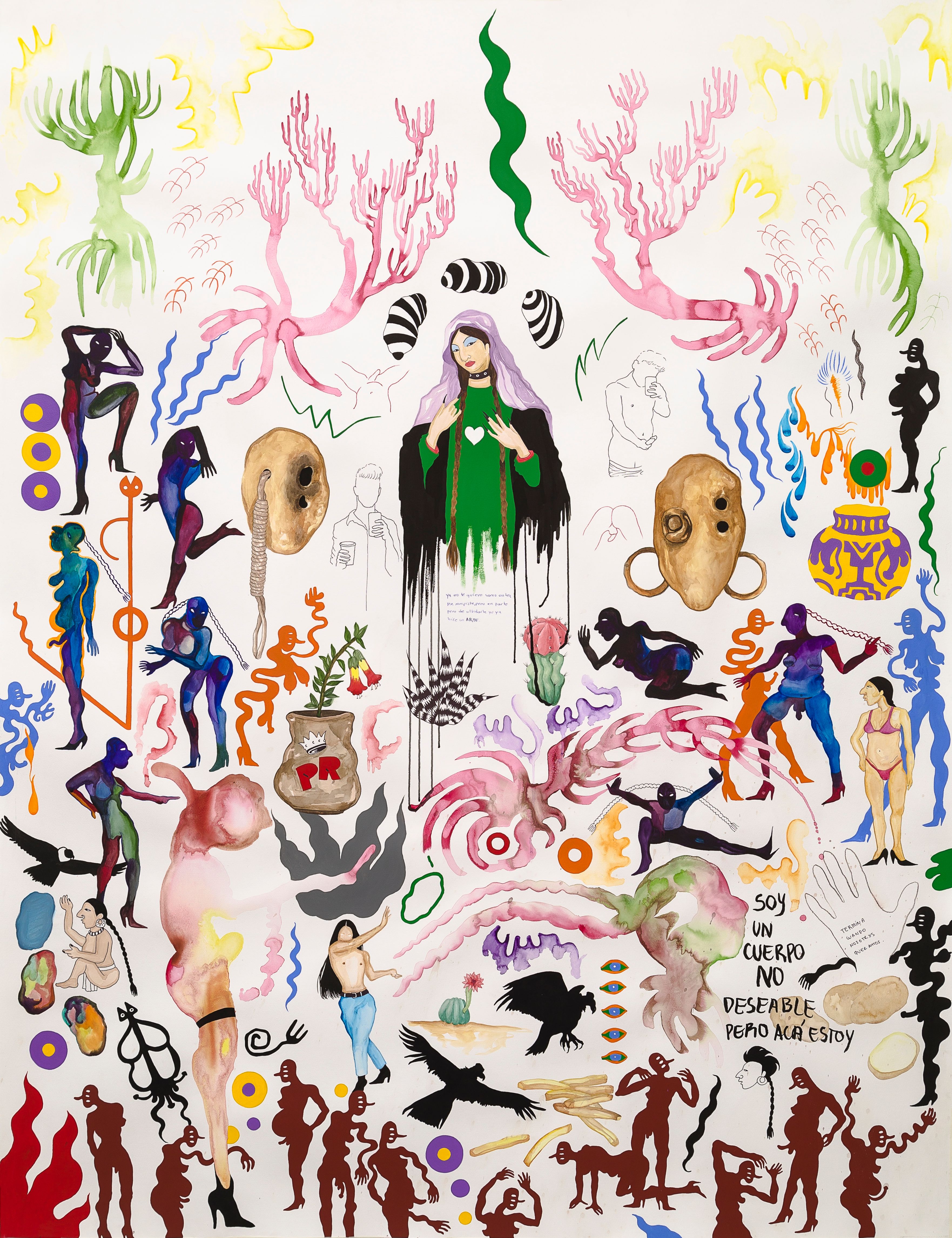

What La Chola recognised in Guido’s painting – however successful – was an attempt to disrupt. This desire is channelled into series of watercolours, Virgenes Cholas, which will bepresented by PASTO at Untitled Art. Almost two metres high, they depict in diaphanous, generous strokes an intricate visual vocabulary. Swords, indigenous jewellery, plants, animals, religious icons, and virgins appear alongside personal representations from the artist’s daily life. “Lovers, song phrases, symbols, and people merge into new forms. I am interested in thinking that we are something more than a body. We flow, we transition, we change.”

Also recurrent throughout La Chola’s works is the potato – an interesting metaphor since it is a tuber native to the Andean region that was later adopted and adapted into Spanish cuisine. There is also word play – papa, translating as potato, father, and the Pope. “It reminds me of the absence of my father, who I met when I was 20, 21 years old, and with whom I had a brief relationship. It represents for me the abandonment, the emptiness, the silence to be filled. When I join the Pope and the cross in a composition, I think of colonialism in its relationship with the territory and the bodies within it.”

Mormons, genitals that merge with other forms, bodies with different sexual organs… I am interested in representing transwomen and cis-gender women subjugating men. We continue to be the object of patriarchal violence.”

In the context of a commercial art fair in a western country, isn’t it difficult to reconcile the political pulse of the work with their presentation as objects for sale to a largely foreign audience, I wonder? But La Chola sees no contradiction – rather an opportunity to expose the issues she is interested in, to reinvent, and to disrupt just by the rich complexity of her presence. In a drawing from Virgenes Cholas one line strikes me: I am an undesirable body but here I am.

Charlotte Jansen is a British Sri Lankan arts journalist who has written for The New York Times, The Guardian, The Financial Times, British Vogue, ELLE, Frieze, The Art Newspaper, and Wallpaper* magazine, among others. She is the author of two books on photography: Girl on Girl (LKP, 2017) and Photography Now (Tate/ilex, 2021). She is the host of the Dior Talks podcast series 'The Female Gaze'.