24 is one year younger than a quarter of a century. For those wanting to calculate age and artistic careers in tandem with one another, it’s easy to assume that being young does not go hand-in-hand with a world coated in generational hierarchy, where curricula vitae as extensive as a multi-page manuscript is a requirement for validation or where value is assessed through the acquisition of artworks for private or museum collections. Emerging, mid-career, established: these are tried and true categories of the contemporary art world and artists working within its infrastructure. Emmanuel Massillon, it seems, then skipped the line and bypassed traditional and necessary hurdles to present at Untitled Art fair with Galerie Julien Cadet. How can an inner-city, DC-born and raised Caribbean kid reach such ranks and strike a chord with work that dismantles and disturbs through medium and subject matter? What’s so poignant about the work, and why must it demand our collective attention?

The answers to the above questions are not as simple as yes or no. So used to being told “no” at such a young age, Massillon’s mixed-media sculptures and paintings are disruptive. They are actively doing the work of not waiting for an answer of validated acceptance. His work confronts viewers to question one’s relationships to objects and how upbringing as fueled by circumstance can impact an individual’s worldview. As evidenced in his work at Untitled Art, Massillon is not haphazardly on view for pure shock value and to momentarily strike your eyes as you try to navigate the chaos of the fair and attendee crowds.

Following a solo exhibition at Swivel Gallery in New York City, Massillon credits the power of Instagram direct messaging for how he came to be represented by Galerie Julien Cadet. Mathieu and Julien, co-founders of Galerie Julien Cadet, said of the artist: “We are really excited to work with Emmanuel Massillon. Since the beginning, we were fascinated by his potential and his clear vision of what he wants to create, and most importantly, what messages he wants to convey through his art. He doesn't shy away from taking the taboo subjects from the everyday life of the African American community and analyzes them through his artistic creation. We had very positive feedback about his solo exhibition that we hosted in our gallery this year. Emmanuel himself being a very charismatic person, his art equally has this captivating and thought-provoking quality that many people feel connected to.”

As explained by the artist himself, there’s an order to the chaos in what’s to be shown at Galerie Julien Cadet’s booth at Untitled Art. Massillon details: “Everything I make has a story. There’s not one object I make or create that does not have an elaborate narrative. Be it African history or inner-city culture, let’s actually make an exhibition with context. A lot of my work stems from the inspiration of being a sample producer – sampling from different artists, different genres, different life experiences. It can be a song I heard, a meme, a fact of African culture. My work is so broad, that one booth would not give that necessary context. When I visited Untitled Art in 2021, I observed the rotating exhibitor booths and gained a recognizance for when it would be my chance. Now I turn to the music ideology behind records having two sides to their one structure. Two different exhibitions in one fair as the days play out and pass by. ‘Side A’ being an overview of my practice, while ‘Side B’ is installation-based and purely conceptual.”

Raised in Washington D.C., Massillon’s lived understanding and experience of the rough nature and realities that plague inner-city American neighborhoods permeates into the compositions and titles of his works. The digestible medium of sunflower seeds in Sodium Craving, 2022 overwhelmingly piles on a canvas around a black and white image of a traditional African sculpture at the bottom of the work, visually alluding to the troubling intersection of healthy food options available to Black communities who exist in lower socioeconomic levels of contemporary American society. The saltiness of the sunflower seeds is overbearing in numbers on the canvas, and the bountiful quantity is contrary to this idea of America's poor not being able to put food on their tables. Yet it’s the damaging amount of sodium in what is available to the community that ends up creating a systemic, vicious cycle for Black bodies that crave what harms them in the end.

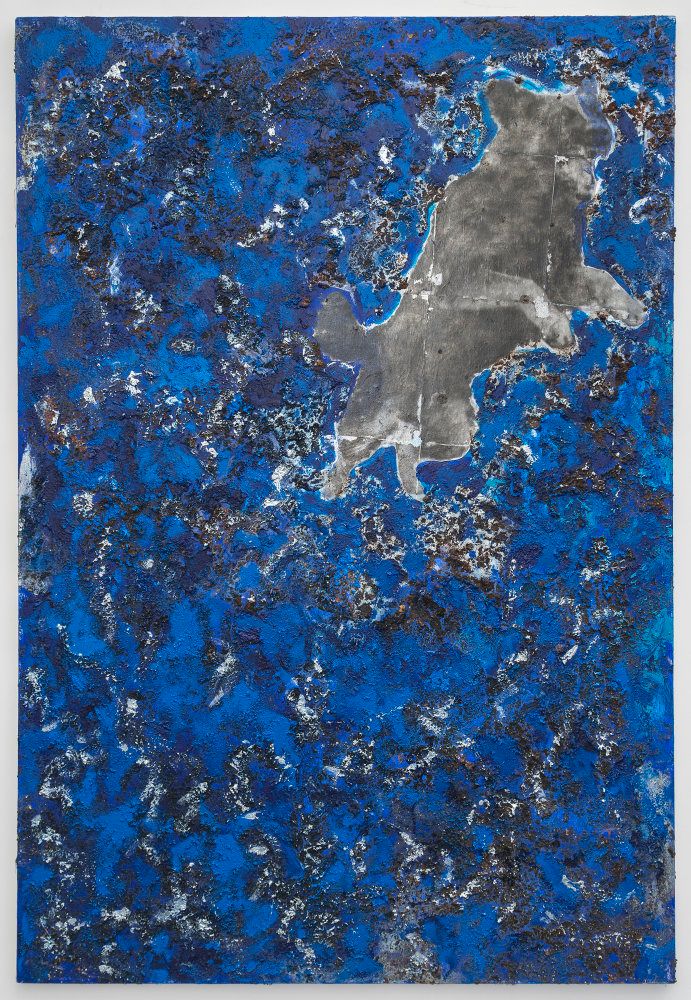

Juxtaposing the dual-sided polysemous verbiage behind his titles, such as the Dog Food painting series that plays on the idea of dog food as a slang for heroin and wanting to literally scratch and itch your skin for that “food” as fuel to live, Massillon catalyzes his fascination for the musicality in hip hop through the ironic titling. He says: “I can’t rap, I don’t produce music. How do I bring that ideology that inspires me so much into works that don’t make sound? It’s through the titles that have more meaning than it initially leads you to believe.” The horrors of drug addiction are transparently masked by the everyday meals of four-legged canines, who were a force of terror against Black bodies during the Civil Rights Movement, begging a viewer of the work to contextualize their own held and practiced identity privileges. Who are you when you walk through an art fair? What meaning do you give an everyday object? What does that say about your own life and where you come from? The high stakes and temporary nature of a contemporary art fair tends to create a financial abyss that lies between collectors and artists, between exhibiting galleries and locals, between those able to buy a ticket or secure a VIP pass and those walking outside the fair wondering how they can afford to enter.

For Massillon, the awareness that many of these inner-city issues might go over the heads of visitors who have never faced or lived in these communities is one that nourishes the very mission behind his work as an artist. As the artist explains: “[My purpose is] ‘to be a voice for people who don’t have a voice. It’s a way to record history. There’s a push to remove Black history out of textbooks, and that’s why it’s the job of the artist to record history.” Rather than seeking to please the eyes of visitors, Massillon becomes an educational channel in which one can peer into in order to comprehend the grim truths of today’s America. An art fair is not an oasis to escape these deeply rooted and systemic problems, and through found objects and recontextualization of materials, Massillon disrupts that false illusion of peace.

Held in Florida, a tumultuous state in itself, Untitled Art takes place annually on the sands of Miami Beach – a place clouded by the fact that it is geographically removed from the inner-city Miami neighborhoods that Massillon’s showcase will shed light indirectly on and about, the unspoken “segregated” districts of the city such as Little Haiti, Miami Gardens, Liberty City, Allapattah, Overtown, and Brownsville. The isolation of Miami Beach as an island away from the mainland is not synonymous with the chemical makeup of those who comprise the majority of Miami’s population: exiles and immigrants from islands in the Caribbean. To be Caribbean in Miami is integral to the bloodstream that powers the region and the intergenerational rituals that are worshiped over time through the past, present, and future.

The older generation in Massillon’s family is another major influence on his work, especially palpable in the woodworking skills taught to him by his grandfather. These skills trickle down into Massillon’s practice through carved and sculpted totems bearing found horns and African idols. The work is kismet in where it will soon be shown, a land just a skip away from the artist’s own ancestral roots. Speaking on the power of Thornton Dial and Bill Traylor as Southern Black artists repurposing found objects as unconventional art supplies, Massillon points out the undeniable comparison of growing up in beleaguered neighborhoods and the ingenuity of Southern Black Art. “We don’t have a lot, but we’re going to make beautiful objects with what we have. Growing up in the inner-city, I always saw people turning nothing into something. The lineage of Southern Black artists doing assemblage… it was just so fascinating to me to see them taking old tires or tubes and turning them into beautiful objects,” he states.

While currently studying for a Bachelor of Fine Arts at the School of Visual Arts, New York City, Massillon still considers himself a self-taught artist, schooled by his upbringing. Rather than generalizing his experience as that of all inner-city individuals, Massillon is a singular conduit into the musings and workings of those navigating these landscapes. Like a wolf in sheep’s clothing – an idiom that aptly fits the artist’s work of a taxidermized wolf covered in cotton to resemble the wool of sheep, with cotton alluding to the cotton crop as an economic force that increased the demand for slaves – Massillon is not to be taken lightly as merely an emerging Black artist. Rather than letting you pass him by, he’ll nip any preconceived notions and assumptions in the bud through a dual-sided body of work that agitates the art fair’s exhibiting composite. His work sends messages that should be heeded closely: “I maneuver through the art world like I maneuvered inner city life in D.C. It reminds me of playing basketball in those neighborhoods and the innate competitive nature within me. We’re just going to disrupt stuff. It doesn't matter that I’m young. It’s unheard of to be from inner-city DC at the age of 24 showcasing a solo booth at a fair as prominent as Untitled Art. We young, and we doing it by not only sounding the alarm but by being the alarm.”

Isabella Marie Garcia {she / her / ella}, or Isa, as she prefers to be called, is a writer and film photographer living in her native swampland of Miami, Florida. For the past four years, Garcia has worked with local and national arts-based organizations such as Burnaway, Opa-locka Community Development Corporation, LnS Gallery, and UNTITLED, Art. Her writing has appeared in publications such as The Art Newspaper, The Miami New Times, and So To Speak: A feminist journal of language and art print publication. Produced in November 2022 through Miami-based non-profit O, Miami, a recent ekphrastic collaborative work featuring Garcia was printed and published in On / Off-Shore: Poets of the Caribbean and Caribbean Diaspora, a multilingual anthology of poetry by Caribbean writers and Caribbean diaspora writers living in South Florida. Garcia graduated summa cum laude with her Bachelor of Arts in English from Florida International University in 2019. More information on her work can be found at isamxrie.com and anywhere through @isamxrie.